"Those who would give up essential Liberty, to purchase a little temporary Safety, deserve neither Liberty nor Safety." — Benjamin Franklin

THE SHATTERED PANE

There is a distinct feeling of insecurity that hits you when you walk through a neighborhood marked by graffiti, decaying infrastructure, and boarded-up windows. You get the sense that crime is ignored, and you feel unsafe knowing that if no one is willing to stop the vandals, no one is likely to stop the thug coming for your wallet.

This is the core of "Broken Windows" policing, the theory introduced in a March 1982 Atlantic Monthly cover story by James Q. Wilson and George L. Kelling. It posits that a sense of order within a community can deter would-be criminals. Based on the evidence, this is very likely the case. Yet as we strive for an orderly society, we must insist that those we empower to protect our rights do not use that authority to usurp our liberty.

THE STATISTICAL MIRACLE

In 1990, William Bratton became chief of the NYC Transit Police. A firm believer in the work of Kelling, Bratton looked at the disarray of the subway system and saw an opportunity to test his theory of Broken Windows policing. The subway system was littered with graffiti, and an estimated 250,000 people per day were jumping the turnstiles. Bratton empowered officers under his authority to start cracking down on petty crimes with the suspicion that this would reduce more serious crimes. He found that 1 in 7 of the jumpers had an outstanding warrant. Within a year of implementing the policies, subway crime was down 30%. The data was clear: stopping the minor crimes caught the major criminals.

In 1994, newly elected Mayor Rudy Giuliani hired Bratton as Police Commissioner to bring this strategy above ground. They aggressively enforced laws against loitering, disorderly conduct, and public drinking. The system worked. Over the next decade, New York City experienced a miracle: homicides plummeted by over 70% (from 2,245 in 1990 to 673 in 2000), and overall violent crime fell by 56%, far outpacing the national average.

THE CONSTITUTIONAL TRAP

However, this statistical miracle created a massive negative externality: the erosion of the Fourth Amendment. As the philosophy of Broken Windows evolved into the tactic of "Stop and Frisk," the legal standard for police intervention quietly shifted. The Constitution requires probable cause to conduct a search—concrete facts leading to the belief that a crime has been committed. Under the pressure to maintain total order, this slid into reasonable suspicion, a lower, vaguer standard that allowed officers to detain citizens based on little more than a hunch or a profile.

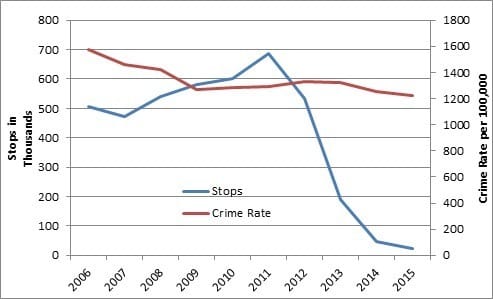

This shift resurrected the specter of general warrants, the British colonial practice that empowered soldiers to search homes and persons without specific justification—the very abuse that inspired the Fourth Amendment. Yet in 2011, at the height of Stop and Frisk, 685,724 people were detained with 88% of them being released without being arrested or issued a summons. To put that in perspective, the state had to detain and search nearly nine innocent citizens just to find a single infraction. This wasn't policing; it was a dragnet.

Statists argued that if we stopped searching innocent citizens, chaos would ensue. The data proves them wrong. As shown in this chart, when New York City ended the unconstitutional practice of mass Stop and Frisk, the murder rate didn't spike—it continued to fall. We did not need to sacrifice our Fourth Amendment rights to be safe.

When the state sacrifices the liberty of the innocent to catch the guilty, it ceases to be a guardian of the law and becomes a violator of it.

ORDER THROUGH LIBERTY

The tragedy of the last forty years isn't that the "Broken Windows" theory was wrong; it's that we assumed only the State could fix the glass. We delegated the responsibility for our neighborhoods to a militarized bureaucracy, rather than the community itself.

True order is not imposed from the top down; it is built from the bottom up. In her seminal work The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Jane Jacobs coined the term "eyes on the street." She argued that public safety is best maintained not by a police officer on every corner, but by an engaged community of shopkeepers, pedestrians, and neighbors. This is organic surveillance, driven by social pressure rather than state force.

Furthermore, private property incentives solve the "broken window" problem instantly. A private owner fixes a shattered pane immediately because it affects their property value. Public officials lack this incentive. By privatizing more public spaces and empowering communities to self-regulate, we align the incentive to maintain order with the right to liberty.

Ultimately, we must demand policing that focuses on behavior (aggression, theft, violence) rather than status (loitering, presence).

The core concept of Broken Windows is sound. As a society, we should shame the vandals who break windows, jump turnstiles, and litter the streets. The problem arises when we allow law enforcement to push the boundaries, sending us down a slippery slope. An orderly society is the goal, but we must insist it is achieved strictly within the confines of our Constitution. After all, the Bill of Rights did not grant us our rights, nor does it limit them; it serves as a restraint on the government, specifically directing them not to infringe on the liberties we already possess.